While searching for an excerpt on music from Plato’s Republic, I found myself reading these words from the foreword of Oliver Strunk’s Source Readings in Music History, a landmark anthology published in 1950 that, for decades, was de rigueur for music majors to study.

[A]t certain moments in its development, music has been a subject of widespread and lively contemporary interest, calling forth a flood of documentation, while at other moments, perhaps not less critical, the records are either silent or unrevealing—this is in no way remarkable, for it is inherent in the very nature of music, of letters, and of history.

By “flood of documentation,” Strunk meant the written stuff of history—letters, pamphlets, posters, ticket stubs, newspaper reviews, and whatever else used to circulate freely in written form. Yet there are times when history leaves a limited record of important developments, making the historian’s work more difficult.

When a college student, I likely skipped over these words in Strunk’s foreword. In fact, I did not read forewords, even those written by a second eminent person, as forewords often are. I had to get to the “real” assignment, like deciphering an excerpt from Franco of Cologne’s Ars cantus mensurabilis (or whatever else helped me survive class the next day). Even if I had read this foreword, I would never have made it to the final paragraphs with its “boring” list of persons whom an author thanks.

Today, I linger on such forewords, prefaces, introductions, and especially on their last paragraphs. Within these, the real story of a book will be found. The heritage and lineage, the rationale, the limits and discoveries, and the entire spirit of what follows will be disclosed. For example, in this same foreword, Strunk refers to the advice emanating from his illustrious father, William Strunk, Jr., Emeritus Professor of English at Cornell, whose classic book Elements of Style used to be the first stop for anyone seeking to write well in the English language. Within a few words, Strunk gives a picture of what must have been his remarkable family of thinkers.

Strunk thanks a coterie of master-scholars who began their extraordinary careers around the period of World War I and continued shaping music scholarship up to the time when I, myself, entered colleges. He mentions names like Alfred (not Albert) Einstein, Paul Hindemith, Dragan Plamenac, Otto Kinkeldey, and Paul Henry Lang—men without whose work our modern understanding of music’s history would not exist.

Yet music majors today are not likely to encounter their names (with the exception of composer Paul Hindemith) not, at least, until they plunge into Ph.D. work and perhaps not even then. Alas, the tireless achievements of one generation seem destined to fall victim to the same fate as paper documents that crumble, fade, or wash away.

Except that we all ride on such scholars’ shoulders, whether we realize it or not! Or at least, we used to ride on such shoulders until our reading levels fell, our attention spans evaporated, and our curiosity died, trapped in the throes of tiny digital screens. Lickety-split, we began voting with our fingertips: if knowledge didn’t pop out after a click on a website like simple.wikipedia.org, then maybe the whole thing was just too hard.

But for a moment, let us crank back to Memory Lane, and remember how this mysterious thing called learning used to work. As serious students we desired to achieve an understanding of our disciplines—in my case, the initial need was to craft an ever-more intricate timeline of music’s development. Consequently, from a book like Strunk’s anthology, I scrambled to paste whatever I could understand from its excerpts onto the ribs of an invisible timeline. If I just kept eating up the contents of such books, I reasoned, eventually I would own the “knowledge” inside.

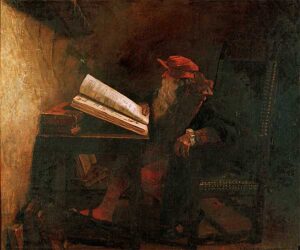

And this approach does work for most of us . . . until it doesn’t. We chew and swallow information for years until one day, somewhere around our mid-life, we are forced to admit that there will never come a day when “knowledge is all mine!” Dr. Faustus tried that and found it thoroughly unsatisfying.

What happens instead, it seems, is that we study in certain ways until we hit a sweet spot in our lives. After settling into that sweet spot, we begin to read for other reasons. For me the chief drive in reading now is to enhance my perspective. Yes, I still need to read for information. Catch me sometime when Smithsonian Journeys has just assigned me a new route to places I have not yet been. I tear through books as fast as UPS will deliver them.

But otherwise it is perspective I crave. The Latin roots of this term born in the medieval science of optics mean “to look through” as we might look through a window. We are outsiders who peer into a subject to see what is inside.

Perspective is a gift accorded us in life, if we are fortunate enough to live out our natural years. Perspective from reading means I get to invite the author to sit in an armchair across from me and begin to talk. We may agree; we may not. But we are engaged in a dialogue and that dialogue becomes an end unto itself.

So it is fine when a book supplies new information. It’s grand when it confirms or challenges my ideas. But my heart longs for a book to strengthen my perspective.

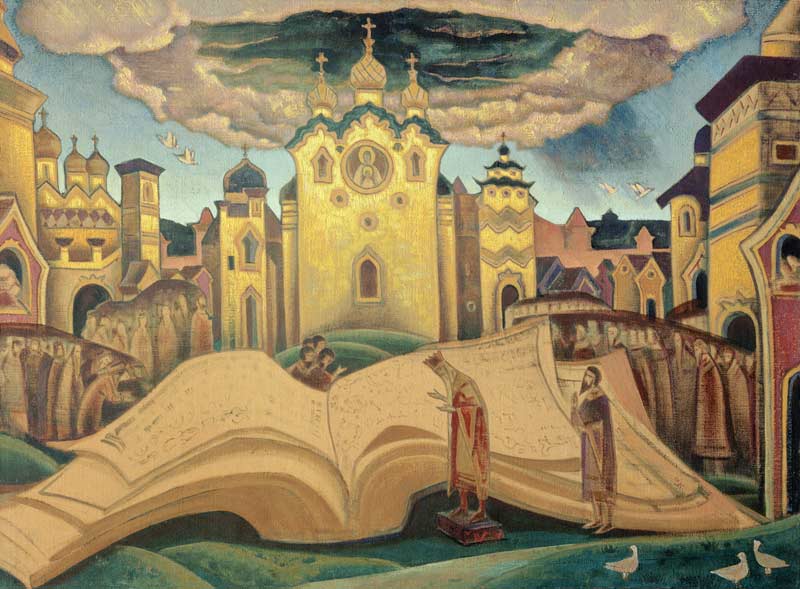

Consequently, I adore revisiting the glorious scholarship of my teachers’ generation, and their teachers’ generation, raked together from the shadows of the past and from the refuse of two devastating world wars. Opening the pages of their books feels like plugging a charger into my soul. These scholars labored for many reasons, but a main purpose was to pass their learning as a legacy to people like me. They knew all too well what the presence, or lack, of knowledge of one’s heritage means, particularly in times when the destruction of heritage raged all around them.

I doubt they would be surprised by the destruction that rages right now. Their version of it had different names and different costumes. But the evisceration of history will always smell, taste, feel, and sound the same, no matter when, where, or how it occurs. And its roots in ignorance and lack of perspective do not change either.

This is a great post, thank you! I agree with so much of this and as a college student, I accept the reproach—I’m going right back to the forwards of my textbook to read it.

Thank you for writing such deep information Professor Carol.

As I’ve been participating in your digital courses I’ve been thinking at a deeper level and sharing information that was not part of my education growing up. As much as the digital age can be disruptive, I have access to writing, music, art, history that draws me into deeper thinking on life’s matters. It is so satisfying.

I’m thankful for people like your husband and you; willing to use the internet for the good.