Wednesday of this week, February 2, was Candlemas. This liturgical event, also known as the “Feast of the Holy Encounter,” officially ends the Christmas season. Flourishing especially in Medieval England, Candlemas begins with the annual blessing of candles for the church’s use, as well as blessings for the stores of candles used in individual homes that would be brought to the service. The text of the service also commemorates the ancient Jewish tradition of purification for a mother who had given birth forty days previously; hence, the additional title “Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary.”

But the greatest focus of Candlemas falls on the story of baby Jesus and his presentation in the Temple on the customary fortieth day after his birth. This presentation ended up more dramatic than his mother Mary expected, since the infant was publicly recognized for the first time as the Messiah by two old people considered to be the last prophets of the Old Testament: one named Simeon, who had been promised not to see death before laying his eyes on the Messiah, and the other, an old prophetess called Anna who lived in the Temple.

The dramatic connection between the very young and the very old in this story has long intrigued artists. In addition, Simeon’s words “Now Let They Servant Depart in Peace” as recorded in the Gospel of Luke (Nunc Dimittis, Luke 2: 29-32, the Canticle of Simeon) have inspired composers to create a host of musical settings in virtually every style.

One of these settings was sung last night, but the real musical highlight came not from the Nunc Dimittis, or even the lovely rendition of Handel’s chorus “Deck Thyself, My Soul, With Gladness,” but rather from the singing of the Missa de Angelis—a full monophonic chant setting of the mass that dates back to the 9th century.

I try not to overuse words like “gorgeous” but, sometimes, honestly, gorgeous is the only word to use. True, our church is blessed with a fine choir, a superb choir mistress, and a tremendous organist who chants just as beautifully as he plays. We also have the architectural advantage of a “cathedral-type” sanctuary for which someone, at some point, had the wisdom to forego pew cushions and carpet, leaving nothing but hard surfaces against which music can vibrate. Still, the Missa de Angelis would move heart and soul if sung half-voiced by someone sitting quietly, alone, beneath a tree.

So, the beauty of Candlemas last night really did engulf us all. Yet, isn’t it odd? No matter how engaged we might be in such a service, a floaty, stream-of-consciousness monologue can still manage to poke itself between the cracks of the mind. At least, that happens in my mind.

This is where Anna Karenina comes in. I’m five weeks into teaching a course devoted to “Imaginative Literature” of the 19th century for the Masters program in Classical Education offered by Memoria College. We just spent four weeks on Goethe’s Faust, a single week on Gogol’s bitterly hilarious story The Nose, and now will launch four weeks dedicated to Tolstoi’s Anna Karenina (Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov and Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard will follow).

Anna Karenina is one of those masterworks that gains depth every time a reader reapproaches it. Including what some call “the greatest novel ever written” in this course has given me a good excuse to buy every translation I lacked, including a snazy dual-language version to replace the crumbling Soviet-era Russian edition I hauled back from the USSR exactly forty years ago. (Hmm, forty seems to be a recurring theme).

And what better reason could one find to buy more books of analysis and criticism for all of the works I mentioned, including a recent title Creating Anna Karenina by Bob Blaisdell (Pegasus Books, 2020)! Blaisdell is a devotee of this novel—someone who, after reading Anna Karenina in English multiple times, bit the bullet and learned Russian in order to read it in the original language (something he’s done now about 11 times). It takes a lot of love to do that!

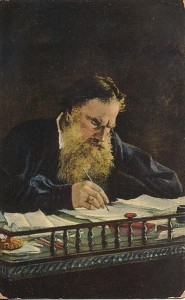

Creating Anna Karenina is a fascinating read, I must say, although you have to be up for a deep dive to take it on. Basically, the author amassed a tedious amount of primary and secondary material to track the day-by-day stages Tolstoi experienced in writing Anna Karenina. Reading Blaisdell’s book feels kind of like spying on Tolstoi’s mind.

And, yes, it was prose on two specific pages from this book that crept into the cracks of my concentration at Candlemas, namely passages on pages 28 and 29 that I had read right before driving over to the service. These passages made me so happy, confirming what I knew, but could not “prove” within the context of a formal class lecture: namely that Tolstoi leaped into writing Anna Karenina in large part because of the inspiring voice of the master of all Russian authors: Alexander Pushkin. Here’s what happened.

Literally on March 18, 1873, a day documented by Tolstoi himself, the forty-four year old author doused himself in the morning with reading some of Pushkin’s golden prose. Suddenly he sensed that a long-endured, painful block hindering his effort to write an historical novel about Peter the Great in the style of War and Peace had simply fallen away! Evaporated, if you will. And in its place, a completely new story-line beckoned him.

Understand, please, that Tolstoi had spent more than two years ardently gathering detailed resources for his novel about Peter’s life and era. He had started drafting this project at least 33 different times and complained to anyone who would listen about his lack of progress. So you can imagine Tolstoi’s relief (and surprise!) as Peter the Great’s world dissolved and, in its place, arose the vision of a sad, sometimes bitter, novel of love and deception set amidst the swirl of St. Petersburg and Moscow and the natural world of the Russian countryside.

Well, any time I can wave the flag and proclaim that Pushkin is the bedrock of Russian literature, I am happy. Tolstoi seems to have been rather giddy himself on the day the breakthrough occurred: he wrote letters to two confidants narrating just how Pushkin’s voice had sprung the lock and released him from his slough through Peter the Great’s life.

By the way, Tolstoi’s initial concept for Anna Karenina (many drafts away from that title or even a recognizable version of the characters) was circumscribed. He predicted the final draft would be completed in two weeks! Scholars believe Tolstoi likely had in mind a “novella,” a literary form he had written with commercial success already. But as we all know, short projects can turn into long commitments. Ultimately, it took four-plus years of sometimes fruitless, often sporadic, always passionate work to bring Anna Karenina to fruition. Sometimes it’s better when we don’t realize what we’re getting into.

I cannot explain why the serpentine threads of musical gold in the Missa de Angelis, the spiritual food in the readings and tender sermon at Candlemas last night partnered so harmoniously with my reflections on Tolstoi’s breakthrough with Pushkin, but that is what happened. Maybe things are supposed to come together this way. O Worship the Lord in the Beauty of . . . all that God has provided to inspire us? Could that be? At least, for me, it was true last night, as these disparate ideas wrapped themselves together in the beauty of a candle’s flame.

Lovely post, thanks for sharing!

I need to return to Anna, it’s been too many years. (What is your favorite English translation?) Doing a reading challenge this year that has a category “favorite author of your favorite author” and I think this gives me a good excuse to read more Pushkin, too. Not that I need an excuse.

Had to listen to the Missa de Angelis in preparation for daily Mass today after reading this! Pure beauty! I wish I had time to do the deep dive with you, Professor Carol. But I will content myself with these little tidbits for now. Thank you and Enjoy Anna!

Thanks for refreshing my mind. I know of these things but have not read Pushkin or Anna Karrinna.

Thank you! I recently finished Anna Karenenina for the first time, and am grateful for these additional insights AND how they coincided with Candlemas for you. Also, I loved the reminder of the reason and focus of Candlemas.

Thank you for the comments and the nice question. Hmm, let’s see. I tend to use Richard Pevear & Laura Volkhonsky’s fine translation in the class, as others already own it. The older translations of Louise Maude and of Constance Garnett still read very well too. Granted, you can find all kinds of “flaws” in the older translations if you want to look at it in a modern-scholarly way, but our ideas of translating, and what is a good translation, not to mention the English language itself, have changed a lot in the intervening decades.

I’m fond too of Rosamund Bartlett’s recent translation (c. 2014) and, because she is such a fine scholar, I might be inclined to “require” it as the one we use for a course, except for the fact that so many people already own a copy of this novel and one wants to respect that and not add unnecessary purchases. Sometimes my favorite translation is which ever one I can fin !

You can find a surprising (to me) number of articles, lists, videos, even, by all kinds of people discussing the whole issue, comparing passages. They are fun to read.