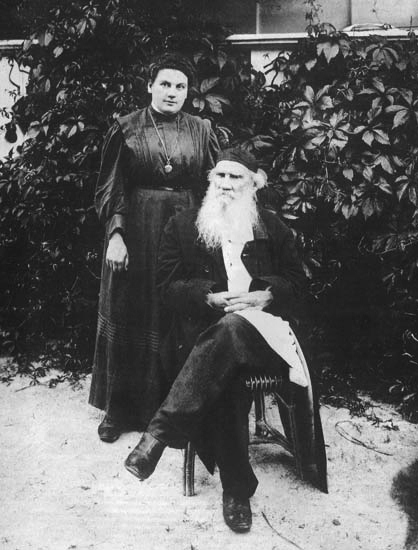

Stories of the family members of “great artists” can be more interesting than the artists’ biographies themselves. It is hard to top the story of Lev Tolstoy’s long-suffering, dutiful wife and editor Sophia Tolstaya (1844-1919) who bore him 13 children, tediously recopied and made literary sense from towers of chicken-scratched drafts for his early novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, and ended her life reviled by both him and his band of fanatical followers known as “The Tolstoyans.”*

But even more interesting to me is the life of his youngest surviving daughter Alexandra Tolstaya (1884-1979). Once old enough to do his bidding, she served as the right hand of her father, adoring him and making the logistics of his life work. After his death in 1910, Alexandra’s path became difficult. Bereft of her primary focus (the well-being of her famous father), she found little appeal in ordinary choices like marriage. So, during Russia’s disastrous campaigns in World War I, she served as a nurse on the dangerous Turkish and German fronts. Later, when the Bolsheviks began to devastate Russia by sweeping away not just Russia’s tsarist past, but her religious, cultural, and economic foundations, Alexandra tried to fight back.

But it was useless. She was arrested five times by the Bolsheviks and imprisoned in 1920. After her release, she, as titular head of the Tolstoy Museum at the family estate Yasnaya Polyana, had to watch her father’s beloved principles be appropriated by Marxism.

Finally she was lucky to get out of Russia. She spent 20 interesting months in Japan. Then she found a way to sail to the West Coast of the US. She had certain friends and contacts here, but spent many years in desperate poverty, relying on sporadic income from lecturing about her father while trying to transform a series of ramshackle properties into marginally profitable chicken farms. Alexandra’s ability as an older woman to do hard farm labor was astonishing. But, after all, she was Lev’s daughter.

Alexandra took every opportunity publicly to proclaim as disasters all that had befallen Russia since the 1917 October Revolution. Who better could give witness to the death and destruction wrought by the Communists? Who better could explain the cruelty of Marxism, the poison of Communism?

Yet the intellectual elites hearing her had absorbed the myths of Bolshevism. Even when provided facts and truths, they preferred their fantasies about Communism.

At public lectures, some pelted Tolstaya with the Soviet’s own propaganda about how “the Bolsheviks were improving the lot of workers” and “making life in Russia more just.” Her own experiences of being imprisoned by these benevolent Bolsheviks, watching the best and brightest arrested, executed, or sent into Siberian exile, while the everyday Russian was stripped of his wealth to benefit the cravings of the Communist oligarchs, made but limited impact.

When Alexandra first sought refuge in the United States, Western governments were undecided whether or not to recognize the Soviet Communist government. The world was watching to see what America would do. The thinking on the Left went like this: “We cannot expect to influence or moderate the Communists if we do not establish working relationships with them diplomatically.”

She countered this reasoning as clearly as she could:

Will the [world] governments really continue calmly to sign trade agreements with the Bolshevik murderers, so strengthening the latter’s position and undermining their own countries? Where are you who preach love, truth, and brotherhood? . . . Do you actually need more proof, more witnesses, more statistics?

Anyone walking around today has grown up with Russia as a superpower. Younger people have known Russia only after the changes that ended most of the brutalities of the USSR. Of course, my own life has been intimately bound up with the study of Russian culture, so I find the changes in my lifetime to be astonishing. Today’s Russia is a far cry from the Communist abyss. It has re-embraced its cultural past, supports its traditional values, and has reinvigorated its religious life. Perfect it certainly is not. But lessons have been learned.

It is we in the West who have now lost our way! Many of our intellectual elites are engaged in a tawdry love affair with Communism. They are embracing the same nonsense fed to the outside world in the aftermath of 1917. And the truth tellers—those who know that death lurks behind these lies—are largely ignored, much as was Alexandra Tolstaya.

Consider reading about this interesting woman. Remember that she began life as “Countess Tolstaya,” a privileged daughter of one of greatest novelist of all times, even though daily life at Yasnaya Polyana was shaped by drastic, idealistic self-abnegation. Think of her loss at her father’s death, and her decision to face the horrors of the wartime front. Imagine returning home to be viewed as a criminal by the country that she loved so dearly. What must it have been like to be the “face” of Tolstoy’s legacy at the very time it was being distorted and repackaged as Marxist?

Imagine the experience of being at the brink of starvation and fleeing Russia, only to revel in the cleanliness and abundance of food offered en route to Japan, even in third-class accommodations. Imagine Countess Tolstaya, laboring to make a new life in America as a middle-aged farm woman, torn between the desire to tuck herself safely away and the need to make political assertions her elite ticket buyers did not want to hear. Her frustration was more poignant when she failed to sway academics, senators, congressmen, presidents, and even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on one social occasion.

But she never stopped proclaiming words like these:

Russia has a cancer on her body: Communism. And if this disease is not stopped, I think that it will spread all over the body of Civilization.

It is easy, especially for young people, to glamorize the false promises of Communism. People of maturity have to lie more deeply to themselves to do so. But even a child ought to be able to see through them.

*Updated: Grownups can enjoy an enlightening rendition of the final period of Sophia Tolstaya’s life with Tolstoy in the excellent film The Last Station (2009) staring Helen Mirren and Christopher Plummer.

Carol,

Thank you for this thought-provoking article that so strongly mirrors what we are facing in our country today. Oh that we would listen to those who know, and heed the truth.

One detail: as I googled “The Final Station,” I discovered that it is a video game. The Helen Mirren/Christopher Plummer film, is entitled “The Last Station.”

Thanks for what you share with us!

Great post, thank you!