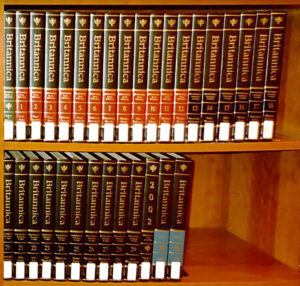

They’re back on the shelf: my set of Encyclopedia Britannica, 14th edition. Bound in brown leatherette with gilded letters, they date from 1966 and weigh a ton. We almost tossed them during our last two moves. Instead, whether due to inertia or wisdom, they stayed in their boxes until a few nights ago.

Why then? Because for the fourth time in two days, I wished I could walk to the book shelf and pull down a volume as follow-up to one of my little granddaughter’s endless “why” questions. Of course there are hundreds of other books right there on the shelf, and often they do nicely. Or, I could lead her over to a computer screen.

But that’s what I’m not going to. I’m sticking to the new plan, which is: unless the web provides a vastly superior resource, the answer is going to come out of a book or from actual experience.

Among the things lost in our Google-saturated world is the tactile joy of opening a massive reference book. These automatically teach patience, perseverance, and diligence. They show a child how to organize complex topics and literally how to see and feel the weight of a subject. Some of the most basic steps in research are taught through reference books, starting with the instructions “see” and ”see also.” Plus, there is felicity of discovering information by accident: looking up “cardinals,” only to have the pages fall open to “catamarans.”

Yes, I know, I know. You can make an argument that “it’s the same” online, that clicking through links on Wikipedia (or even Britannica.com) does the same thing. But these are clicks, not journeys of learning. At least not to me.

I grew up with reference books. When I work online, my mind takes the same visceral journey I learned sitting on the library floor, pulling down volume after volume of reference works. It’s a powerful journey that resonates through one’s entire being.

Encyclopedias long represented the highest aspirations a family could have for its children. My mother agonized over the decision to buy a set of World Book encyclopedias. There was no question that we needed one, but how to pay for it? We did what most families did, paying it out over a year or two. When the last payment was sent, we celebrated the treasures as finally ours.

I found this set of the Encyclopedia Britannica in the late 1980s at an estate sale for an embarrassingly low price. It went immediately to my office at SMU and, along with the 20 volumes of my treasured Groves Dictionary of Music and Musicians, it filled up a good part of one of the bookshelves lining my office. It was well used, particularly during small seminars held around the table in my office.

Then off I went to the ranch, occupied with goats and building Professor Carol. But the encyclopedias still had their place on our shelves. Leaving the ranch, though, presented a strong argument for giving them away (if someone would take them). But laziness prevailed and they got packed. And stayed packed.

Now they are being reborn. And I’ve got a lot of recent company lately in making this move back to actual books. The tactile power of physical books is slowly being re-acknowledged by, at least, some researchers. Who knows? The “tablet” industry may one day be forced to admit that digital screens are a poor-to-damaging medium for teaching young people. Most of us can testify to the negative effects they have on children we know.

Plus, even if all things were equal, what competes with the pleasure of opening a book? Especially a heavy, important book: one that has fold-outs and cellophane overlays for topics like the “human body” and the “planets.”

Would I really choose those aging pages for teaching over the beautiful digital imagery available on line? Plus, don’t I realize that they’re out of date (horrors)? Why, they probably don’t acknowledge that Pluto is / is not / is a planet!

Yes, I’m fine with that choice. I’m pretty sure a four-year old will gain more by manipulating the cellophane overlays to learn the solar system than she would staring at photos from the Hubble Space Telescope, no matter how dazzling. One source is tactile, one is not. One source allows the student to enter at her own rate, quizzically; the other presents images of perfection that easily overwhelm and can just as easily be ignored or forgotten.

The binding is flaking at the top on a few volumes, but the visual impact of the set is beautiful. “Careful, they’re heavy, “I admonish. “They’re grown-up books, but you may use them. Let’s take one and see what we can find.”

They need no cables or recharging. And they are guaranteed not to dampen the sparkle of a little child’s eye the way screen time does. Best of all, when it’s time to close a volume, a temper tantrum is not likely to erupt (you know what I’m talking about).

The biggest problem I foresee will be lifting them back onto the shelf, or keeping them in order. You can’t just close the book and have it disappear into the cloud. There’s a lesson in that, too.

Carol, you are spot on with this. I try my best to have my grandchildren refer to books rather than “research on the ‘net” or “Google it”. The tactile aspect of any book enhances the learning experience and I think helps young people retain the knowledge gained.

So, kudos to you for a very well written hand highly appropriate topic for today’s electronic era. I am sending it to my daughter for her to share with the grandchildren TONIGHT!

Cheers!

Jim

Good for you, Carol. Books are wonderful, and I’d be sad if my grandchildren missed out on the serendipity of looking up one things and finding themselves on a serendipitous journey of discovery. And all without a single clickbait headline that promises much and delivers little. You make me want to go and read encyclopedias!