Standing with a dozen others outside the main administration building, Cooke Hall, on the campus of Highlands Latin School, I watched as swaths of thick clouds chugged past, as if daring us earthlings to catch a glimpse of the eclipse.

Before us, out on the green, a group of middle-schoolers ran about freely playing frisbee. They were certainly aware the eclipse was nearing and had proper paper eclipse glasses (courtesy of a local bank) tucked in their pockets and belt loops. But they were far more concerned with their game . . . unless, or until, something really dramatic happened.

As it turned out, the darkness we experienced was not as drastic as anticipated (despite Louisville being well “in” the eclipse zone). The most impressive part of the experience came from the unearthly colors cast across the campus green as the twilight grew. Headlights of SUVs pulling in to the campus to pick up children added to the light show. And, yes, there were two separate instants of maybe 1 ½ seconds each where I did see a dramatic profile of the sun nearly covered by the moon.

Still, I was happy without those glimpses, taking in the cooling air (and it did get cooler). I had sat for a long stretch since early morning, working almost feverishly on a curriculum project that needed completing yesterday, if you know what I mean. Yet when an eclipse comes, you have to stop writing and go outside, right?

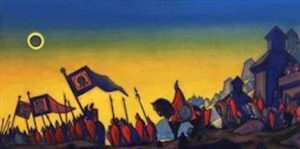

What you don’t want to do is charge headlong into battle following an eclipse! I am referring to the dilemma posed in Prince Igor, a 12th-century historical figure whose ill-fated campaign lies at the center of the earliest documented Russian poetic epoch, turned centuries later into a pageant-filled opera by Romantic composer Alexander Borodin.

Wouldn’t it have been fun to have heard Borodin’s “eclipse music” while we all standing out there? It could have started about six minutes into the Prologue when, at the ceremonial leave-taking of troops amidst the ringing of half-hearted, but sonorous “Slava’s” (Praises) from the chorus, the air starts to shift. Darkness encroaches. The stars come out. Characters glance around anxiously, accompanied by touches of low string tremolos, quiet pizzicatos, and bell-like interjections in the percussion. A unison melody of choral singers whispers the fact that any child then would have understood: namely, this celestial phenomenon was a bad omen for troops about to go off to war.

Wouldn’t it have been fun to have heard Borodin’s “eclipse music” while we all standing out there? It could have started about six minutes into the Prologue when, at the ceremonial leave-taking of troops amidst the ringing of half-hearted, but sonorous “Slava’s” (Praises) from the chorus, the air starts to shift. Darkness encroaches. The stars come out. Characters glance around anxiously, accompanied by touches of low string tremolos, quiet pizzicatos, and bell-like interjections in the percussion. A unison melody of choral singers whispers the fact that any child then would have understood: namely, this celestial phenomenon was a bad omen for troops about to go off to war.

Tension builds until a roar of timpani and cymbals bring the anxiety to a full musical crescendo. Igor, however, ignores his momentary concerns, the pleadings of his wife, and the fears of the women who stand to lose their husbands and sons (they will). As in a Shakespearean tragedy, common-sense wisdom will lose. Proudly, foolishly, Igor heads off with both his sons, a fatal decision for the boys and one that will land him as a captive of the Turkish nomadic tribe known as the Polovtsy.

From an historical standpoint, the whole story is a disaster (although Igor does escape and return home, an action that, in and of itself, was ignoble back then). From a musical view, though, Igor’s capture gives rise to a sumptuously grand act where sensually beautiful melodies and frenzied rhythms fill the stage—music popularly known as the Polovtsian Dances. This is famous music, recognizable by nearly anyone who has ever attended a concert, watched a film, or heard a commercial!

But the eclipse music is not well known. And it’s very good, even if understated. Would I have had the nerve to bring out my JBL Flip 5 speaker and crank up Borodin’s eclipse scene as background to our search of the clouds? Actually, I doubt it. First, speakers, no matter how good, can hardly convey the intensity of orchestral music or choral singing. Secondly, nature was giving us plenty of background music, particularly in the form of one bird who was squawking ceaselessly to the left of the portico. It could be that bird had a nest nearby and simply didn’t like everyone suddenly milling around, rather than sitting quietly in our respective offices. Or maybe this was the kind of “creature response” we had read about: birds twittering, cicadas calling, and a sense of unease in the animal kingdom?

Either way, it was grand to share the viewing, or non-viewing, of the eclipse with such a company of friends and colleagues, particularly in such a lovely spot. I’ve written before of my fondness for being here, on this campus which also houses Memoria Press. They call me a “writer-in-residence” as I spend the days digging away at a project. The title makes me smile, particularly since I spent my life more as a musician-in-residence. Thursday, we’ll tape a podcast which is likely to focus on music, although how and with what degree of unorthodoxy I do not know. After the excitement about the eclipse, my guess is everything else will tend towards the mellow.

All told, my chance to extol Prince Igor in a “classical manner” (surrounded by classical educators) will have to wait until the next eclipse. I am glad, though, to share Borodin’s scene with you. If you’ve never seen Prince Igor, do know that it’s grand and gorgeous (costumes, costumes, costumes), although the libretto moves at a stately pace, so a bit of boning up on the details of the epoch would be a good strategy (not to mention having access to supertitles or a score with English lyrics). Maybe we need to make Prince Igor one of the titles, soon, in our series “A Night at the Opera.” It certainly would be timely.

People are going to remember this eclipse for a while, either because they had a dramatically good experience viewing it, or because they spent substantial time and money to experience it and had to settle for grey clouds and a slight drop of temperature, flanked by others equally disappointed. If in the latter group, they may be cheered by knowing they were spared the terror of ignoring an omen and entering into an ill-fated military campaign in dusty sandals and heavy medieval armor.