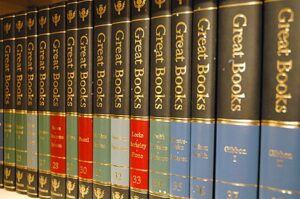

Seeing The Great Books of the Western World spread crisply across the upper shelves of the library at CiRCE Institute’s new headquarters triggered powerful memories for me. Indeed, it was precisely this set of books that, long ago, signaled the existence of a world beyond the simple realm of my childhood.

But first, let me tell you about the occasion that led me to stand before these beautiful volumes. Hank and I were attending the gala unveiling of the new home of CiRCE Institute. Lying in a bucolic spot outside of Concord, North Carolina, the new facility includes a large, camp-style wooden lodge that, through wondrous circumstances, became available to be repurposed by Andrew Kern and his staff. After significant reconstruction and beautiful refurbishing, this marvelous building was set to enjoy its public unveiling that night. Finally there would be space for Kern’s unparalleled vision to soar in even higher orbit!

The night was cloudless and quite cold for early November. A bonfire blazed as a beacon for those coming up the path. Happy voices filled the air. A cornucopia of harvest-themed food and drink was laid out on long, wooden tables. Ebullient speeches were made, concluding with heartfelt words of Kern that, unsurprisingly, evoked a tear in many eyes.

After the formal part of the evening, I joined others to wander down the hallways, peeking into freshly painted offices and future seminar rooms, smiling at the utterly different ways the beloved members of the CiRCE staff were starting to decorate their individual offices. (This sentence means more if you know how staff members were squished in groups into shoebox-like spaces back at their former headquarters.)

Kern had yearned to have a real library when a new home for CiRCE became a reality. And here that library was, the fine bones of his and the staff’s collection already expanding through shelves that ringed the room. Turning to admire titles, I stopped short when I found myself staring directly at The Great Books of the Western World.

It was precisely this publication that turned a key for me when I was twelve years old. The books entered my life at that critical age when, for so many children, core dreams and goals were taking shape. In essence, these beautiful bound volumes afforded me confidence that something beckoned beyond my paltry existence in the small city of Roanoke, Virginia.

I could not have known just how significant The Great Books of the Western World really was. First published in 1954 in 52 volumes, this publication began as a pet project of Robert Hutchins (1899-1977), then president of the University of Chicago. He fully appreciated the offerings of the famous “five-foot shelf” of volumes known as The Harvard Classics (1909)—smaller-format books that had influenced the intellectual discourse in the United States. Still, he wanted to extend and intensify this discourse, and so he worked with the eminent Mortimer Adler (1902-2001) to launch The Great Books of the Western World with the intent that it engage not just collegiates, but also men and women of the community eager to acquaint themselves with the ideas that have defined Western civilization.

But, of course, such lofty things mattered not at all to me in 1964 when I first discovered these shiny books on the shelves of the newly built Williamson Road Branch Library. I knew only that were a fascinating element in the “big” (in truth, small) branch library that miraculously had arisen just three blocks from my home. That meant the library was all mine: no adult had to drive me there.

The contrasts of this new library with its precursor, aptly named the Williamson Road Book Station, were startling. That collection had been crammed into a once-noble, two-storied brick house of 1920s vintage. It was a dusky, dark place with every limit you can imagine. Still, its dim lighting, sharp smell of book dust, and melodious creaking of heavy polished floor boards remain sweet in my memory.

The new library could not have been more different. First and foremost, light poured through big windows, illuminating rows of tall metal shelves. The books’ spines practically shone in rays of sunshine. Also, the “kids’ section” was placed in a separate area. This meant that the books I was beginning to seek were shelved in the “real” part of the library—the adult side.

And yes, it was in that adult side, between the second and third row of shelves, that I found The Great Books of the Western World. All 52 volumes were elegantly bound with quasi gold leafing on the spines. The delicate thin paper revealed small but ravishing print. And, despite not understanding most of the contents, I knew that these books held a key to my future. Had I known more about the mission of Mortimer Adler, I would have realized that I—yes, I—was a younger version of his target audience, now able to receive “the sources of our being . . . our heritage.”

Many an afternoon I pulled volume after volume of these books into my lap. I say “lap” because somehow I decided the spot on the floor in front of these books would be my reading nook in this library. In fact, it was a memory of cold linoleum that first hit me while standing in the warmth of the CiRCE library.

Within the 52 volumes I did find some titles I could relate to back then (Dickens, Austin, Elliot, Twain, Chekhov), as well as the full rendering of documents we had studied in American history classes. A panoply of names like Euclid, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Aquinas, and Blaise Pascal were utterly new to me. Still, they impressed themselves on my brain, despite my being lost after running my finger through the second paragraphs of their writings. It was also here that I first saw the works of Shakespeare laid out on gorgeous paper. And it was here that I realized I had better get going, if I intended to learn about the world.

I wish I had known that Mortimer Adler was just my age when he took one of the biggest steps in his intellectual development, courtesy of a distinct teacher named Mr. Duke (who had one glass eye!). Mr. Duke taught the 12-year-old Adler how to create outlines as a way of elucidating ideas. That skill caught the boy’s imagination intensely. It is, after all, in young adolescence that children catch fire with such passions. Little could Adler have known how his gift for “outlining” would affect American intellectual life.

But all of this brings me back to that moment in the CiRCE library. Andrew Kern walked up behind me. He smiled at my gaze upon these books. “We are old friends,” I said, and told him why. “Ah,” he said, “maybe you ought to write that story.” This, we agreed, was one of those distinct moments when the past and the present clasp hands and melt into a single circle. “Maybe I will write it,” I said.

And so I have.