At social gatherings with colleagues, a common question arises: “What are you reading right now?” Do you find yourself hearing that question also?

How blessed Hank and I are to work with friends who are serious, thoughtful, and well-read. Our dinner conversations regularly turn to serious discussions of literature. My own dive into this literary pool tends to swim in directions different than theirs (Pushkin, Goethe, anyone?), but no matter. We all regret that our lists of unread classics remains too long.

Still, while usually holding back, we often want to ask the next obvious question: “What are you listening to right now?” A couple of times we’ve actually done it! What would you expect the answers to be? With musicians, of course, the answers are likely to be what each person is studying, practicing, conducting, or performing. But from people who take their primary artistic delight in the great literary works of the Western canon, the answer can be a blank stare.

Granted, the question is unexpected. It’s also confusing. The most astute lover of literature may not automatically make a connection between the Great Books and the Great Masterworks of music. A bit of coaxing is necessary.

Beyond that, those who might reasonably say “I’m going to read The Count of Monte Cristo and reread Brothers Karamazov this summer” are not necessarily thinking in terms of adding: “Furthermore, I’ve never watched Verdi’s Otello or a single opera by Handel, so those are on my plate for July and August.”

Yet, is it farfetched to want to hear that answer? Would it be too outlandish to hope for someone to say, “You know, I’ve wanted to revisit all six of Tchaikovsky’s Symphonies, so I’m doing that over Christmas Break”? Should these works not share the same playing field as Homer and Austen?

No, it is not outlandish. It is the next step, as would be the art, theater, and dance that extend the circle of ripples known as the Great Works. Still, little will change without identifying the roadblocks that keep these masterpieces of music off the dinner plates of people who regularly devour the best in literature.

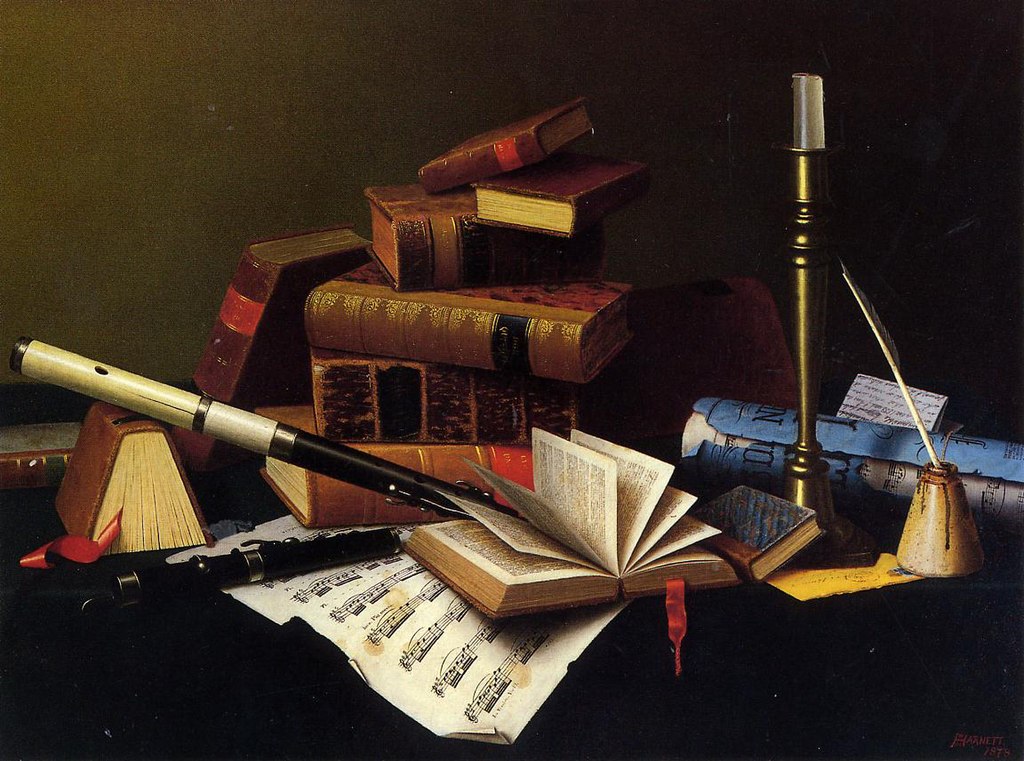

Pieces of music are different creatures from books. Books stand there, their pages tucked quietly between covers. They ask nothing more than to be picked up. Once a person starts to read, he is in communion with the book. Nothing more is needed. Unless someone is a highly trained musician, it is unlikely that the circles and lines on a musical score can be absorbed in a similar way (in fact, they can, most vividly; but this is not an entry-level skill).

Furthermore, reading a book has built-in visceral landmarks and rewards. We see pages passing by. We can put bookmarks to mark where we’ve stopped. We feel the physical weight of the book in our hands. Sometimes it seems to lighten as we draw close to the end—almost as if we need to clutch it closer while the experience of a great read comes to an end.

Music offers different experiences. Emotionally few things are more rewarding than listening to music. Yet, we must either be present for a live performance, perform ourselves, or have a recording play over loudspeakers or headphones. These are more complex ventures than picking up a book.

With music, we know, going in, the number of minutes a composition will take, more or less. That length requires the requisite time and space within our lives. There is no musical equivalent to reading two pages of a novel while waiting for a dental appointment to start, particularly if the thing we’re “reading” is a Mahler Symphony!

Plus, music is too wrapped up in the idea that it is primarily for pleasure and leisure. And of course, that is true to a point. But this fact has led to a limiting of the power of music. It also has led to an awful proliferation of unwanted, ugly and distracting background sounds forced upon us involuntarily in otherwise posh places. We can barely avoid extraneous musical sounds even when filling the gas tank.

Then there is the greatest problem. We learn how to read as we grow. Many of us read regularly, steadily, and built up nuanced and powerful skills at reading. We built up our endurance for reading too. And finally, we built up a treasure chest of references that speak from past reading to enhance the reading we do today. Few adults are taught what it means to listen consciously, in a similar manner, to music.

Looking for the bright spot, though, let us celebrate the fact that great works of music are astonishingly easy to locate and access (this was not true in the past). In fact, entering into the masterworks of music in an ad hoc manner can be rewarding. It requires far less specialized knowledge than people think. Instead, it asks humbly for the same focus as reading a book you might pick up by accident, or upon recommendation. That means overcoming the habit of multitasking, of thinking that music speaks its full message in the background while we do other activities. In fact, listening to music without distractions can be like having a veil lifted off of a darkened stage, so that the real colors shine forth.

None of us will reach the top of the mountain called “Great Works of Literature,” and that’s okay. We comfort ourselves by remembering that the vistas from every level along the slope are amazing. The same exhilaration awaits with music.

If you’re looking for a way to start, consider pairing what you are reading with masterworks of music that express the similar style, theme, or content. Hank, for example, is coming out of an intense reading of War and Peace (in the Epilogue now, I believe). His reading of that novel was partly inspired by his time brushing up on Prokofiev (apologies to Cole Porter) for our Composer of the Month series. I won’t divulge next month’s composer just yet, but that will occupy much of his listening time and it may well determine the next book he reads.

Remember too, we at Professor Carol have lots of resources to help you get started. If the idea of pairing literature and music does not appeal, consider art and music, cuisine and music, fashion and music, or, simply close your eyes, spin around, and point to a type of music, style, composer, that you have never before encountered. Take a nibble. And as you do, share it with others. Let at least one conversation with friends start with you asking the question “What are you listening to now?”