Veni, the imperative form of the Latin verb venire, to come, figures high up in the poetic texts of Advent hymns. For that matter, it lies at the root of the word Advent itself! Most striking of such hymns are these three: Veni Redemptor gentium (Come Redeemer of the People), Veni, veni, Emanuel (O Come, O Come Emanuel), and Veni Creator Spiritus (Come, Creator Spirit), a text also used at Pentecost.

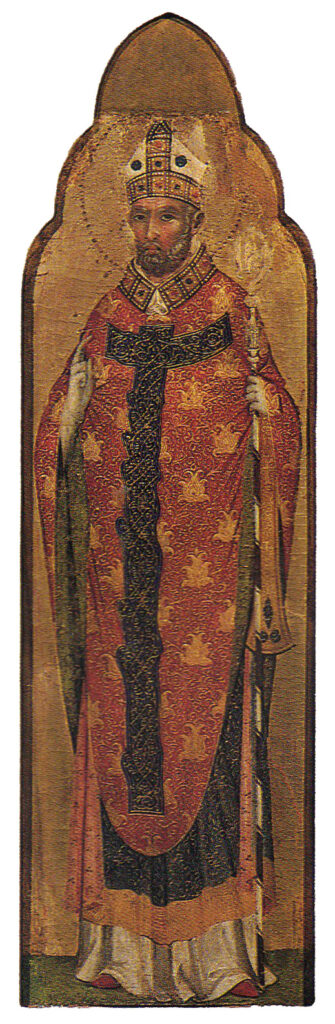

Of these, Veni Redemptor gentium benefits in status from its authorship by the early Church Father Ambrose of Milan (c. 340-397 AD), otherwise known as St. Ambrose. Ambrose was one of an influential quartet known as the Founding Doctors of the Christian Church that included Gregory the Great (Pope Gregory I), Augustine of Hippo (St. Augustine), and Jerome of Stridon (St. Jerome). Considering solely their impact, these four figures would yield a pretty good history of early Christianity.

Rather than come down to us as a scholar, philosopher, or martyr, Ambrose was a public figure famous for denying church entrance to Emperor Theodosius I for his massacre of 7000 people in Thessalonica inside of three hours in 390. Ambrose also had considerable influence over St. Augustine of Hippo, whose writings are still widely read. In addition, Ambrose for centuries held credit for shaping the development of church chant and introducing poetic, non-Biblical hymns into the standard service texts (liturgy).

As an example of Ambrose’s ongoing influence in hymnody, Martin Luther twelve hundred years later took the poem Veni Redemptor Gentium, translated it into German, and gave the world a glorious German chorale often featured in the Advent sections of hymnals: Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland (Savior of the Nations, Come).

One thing modern Western musicology does all too well is debunk honored legends and traditions. Through applying scientific techniques to music research—from carbon dating to high-tech scanning of medieval parchments, to research into the chemistry of inks and bindings, to the mathematical analysis of print fonts and watermarks, exponential amounts of knowledge have been generated about the accuracy of historical details in our Western musical culture.

So, just as Pope Gregory clearly did not write all of the Gregorian chants (we knew that without the science, thank you!), nor did he likely take dictation from the Holy Spirit in the form of a bird singing in his ear (though it makes perfect sense, plus we love the icon portraying this story), so too have certain of Ambrose’s legendary accomplishments been contested and dismissed.

But many still stand, including the penning of at least six important hymn texts, including the one we feature today: Veni Redemptor Gentium. This gorgeous text, set often to the simple, yet sumptuous chant melody below, encapsulates much of what we hope an Advent hymn will offer.

Ambrose’s original poem has eight verses, but the hymn as printed in hymnals today begins with Ambrose’s second verse.

| Redeemer of the Nations come, Reveal yourself in virgin birth The birth which ages all adore, A wondrous birth, befitting God. |

Of the seven verses, I find myself drawn to this one

| Aequalis aeterno Patri, carnis tropaeo cingere, infirma nostri corporis virtute firmans perpeti. |

O equal to the Father, Thou! gird on Thy fleshly mantle now; the weakness of our mortal state with deathless might invigorate. |

Can you find clearer words to describe the state of our world at this point in time? Think how many are now living under severe, even absolute government lockdowns, all the crueler because of the length of the restrictions preceding them throughout this long pandemic. The weakness of our mortal state screams for restoration. Ambrose’s plea that “deathless might invigorate” (virtute firmans perpeti) blazes like a weapon against all that tries to shake our confidence.

Pandemics, epidemics, plagues, invasions, and threats of war are nothing new in human history. But the ability, through the internet, to ingest their details and internalize their terror non-stop puts an unprecedented burden on our mortal souls. How does one get away from the news? How does one clear one’s mind and shake off the sense of foreboding?

I confess to being a news junkie, starting back in my teens when my favored medium was radio. I can try to justify my “junkie” status all I wish, but the truth proclaims something else: my own spiritual peace, and maybe yours too, is not aided by this approach to life.

Certainly keeping our receptors tuned to the rattle and crash of the world blocks anyone’s ability to enter into an effective and fruitful state of devotion. The strength to shut off this noise is not easy to find.

All the more reason why many of us welcome a penitential season like Advent. It turns the page and provides a guide for clearing the air. Entering into the rubrics and momentum of any liturgical season flies in the face of the world’s agenda. It brings a focus that stands in contradistinction to the world’s chaos. The healing that awaits us as we enter into a spiritual season is invisible to those who rejoice in deriding it. And so the skeptics will harumph: “What good does all that churchy stuff do?” That question pretty much proves they’ve never tried it.

Or, to use the words of Ambrose’s Veni Redeptor gentium:

| Praesepe iam fulget tuum lumenque nox spirat novum, quod nulla nox interpolet fideque iugi luceat. |

Thy cradle here shall glitter bright, and darkness breathe a newer light where endless faith shall shine serene and twilight never intervene. |

How good it is that Ambrose’s musical accomplishments ring true and still flourish in Christian tradition. For example, Ambrosian Chant, a sumptuous tradition of Northern Italian plainchant associated with his name, will make a fine topic for us to explore another day.

Meanwhile, do consider listening several times to Veni Redemptor Genitium in its rhythmically free, or chant, style. You will see that Ambrose’s words, when rendered into English, read as “LM” or Long Meter, i.e. four lines of 8 syllables each. This is a standard, natural-feeling, and appealing metrical structure for a hymn text. This also means that Ambrose’s poem will fit beautifully into many other tunes, including modern ones.

Consider singing this poem, then, to uplifting and familiar melodies like Duke Street (better known as Jesus Shall Reign Where’er the Sun), Rockingham (Oh When I survey the Wondrous Cross), Truro (Christ is Alive! Let Christians Sing) and other tunes you will find listed in the category of Long Meter (LM) in the back of traditional hymnals that index hymns by metrical structure.

But do give the ancient chant setting a strong consideration. Chant melodies, intertwined with their powerful words, tend to move easily into our ears, our minds, and our hearts. Effortlessly they take on a life of their own. They love to spring into inner song at difficult times. That is the reason they have endured for millennia.