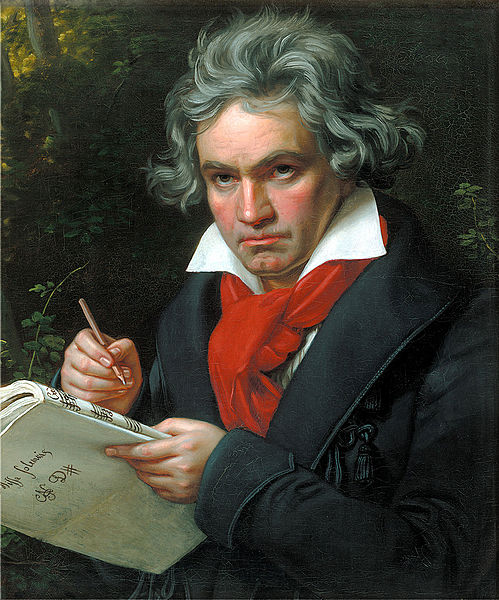

The world will celebrate the 250th anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven’s birth on Wednesday, December 16. An anniversary of this scale for a composer of Beethoven’s standing has led me to frame today’s Advent Post around the joyous Hallelujah Chorus from his sacred oratorio, Christ on the Mount of Olives. Yes, it’s a work for Lent, not Advent, but Handel’s Messiah with its Hallelujah Chorus has become a regular part of Advent and Christmas concerts, so why not Beethoven’s? This oratorio, focusing as it does entirely on the events in the Garden of Gethsemane, reminds us that Christ’s destiny is the Cross, something we can forget when gazing in tender adoration at the Manger.

If the words “sacred music” and Beethoven arise together, people tend to get a puzzled look or else jump to his Ninth Symphony. That extraordinary work has acquired a sheen of religiosity due to its large-scale chorale finale—a first in our Western canon. In that movement, Beethoven set part of Friedrich Schiller’s effusive ode An die Freude (1785), the principal melody of which has become ubiquitous as a hymn under the title Ode to Joy.

If the words “sacred music” and Beethoven arise together, people tend to get a puzzled look or else jump to his Ninth Symphony. That extraordinary work has acquired a sheen of religiosity due to its large-scale chorale finale—a first in our Western canon. In that movement, Beethoven set part of Friedrich Schiller’s effusive ode An die Freude (1785), the principal melody of which has become ubiquitous as a hymn under the title Ode to Joy.

But neither that melody nor Beethoven’s choice of Schiller’s text answers any questions about Beethoven’s own religiosity. Nor, with its infectious lyricism, does that melody reflect the musical and personal struggles that characterized every step of Beethoven’s life.

Raised a strict Catholic, and insisting, in later life, that his ward and nephew regularly attend mass, Beethoven expressed the broader spiritual interests of his day, including admiring certain Protestant literature and expressing some curiosity about Eastern religions. The 19th century, with an aesthetic approach we call Romanticism, simply adored the exotic.

But Beethoven did, at times, write traditional Christian religious inscriptions on his compositions, using words like: “Give thanks to the Almighty after the Storm.” And he did receive Last Rites and a Catholic burial. He also wrote three significant pieces of sacred music: a fine Mass in C Major, his gigantic Missa Solemnis (Solemn Mass), and a ground-breaking oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives (Christus am Ölberge). We will forego the temptations of first two and sample instead a high moment from his lone oratorio—the finale sung by a chorus of angels.

Christ on the Mount of Olives is unusual as a Passion, since the text by Franz Xaver Huber deals solely with Christ’s vigil in the Garden of Gethsemane and his arrest by the Roman soldiers. Beethoven wrote the work in haste for Holy Week 1803 at a time when the oratorio was a highly popular form for Lenten edification and entertainment.

Beethoven had just made one of his hasty moves into new lodgings, installing himself above the same Viennese theater where Mozart’s Magic Flute had had its premiere. In the previous year Beethoven had sunk into despair over his rapidly worsening deafness. Just six months earlier he attempted yet another medical treatment at a healing springs in Heiligenstadt, a small town outside of Vienna. The failure of this treatment brought on a cathartic moment in his life.

In utter distress, he penned one of the most famous letters in all history. We call it the Heiligenstadt Testament and its emotional intensity has been interpreted in many ways, from a quasi suicide note to his brothers to a literary grappling with his personal fate. One thing is certain: he entered into a kind of acceptance of his condition that opened the way to his most fruitful and heroic period of composition: the Third (Eroica), Fourth, and Fifth Symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, superb piano sonatas and string quartets, his only opera Fidelio, and Christ on the Mount of Olives.

Stories about the oratorio’s single day (!) of rehearsal make fascinating reading. The frustration of all involved eased only when Beethoven’s aristocratic patron brought in baskets of fruit, cheese, and wine. That night, a passable performance began at six p.m. and included his First and Second Symphonies, the Third Piano Concerto, plus Christ on the Mount of Olives with its length of approximately 50 minutes. Today we would call that a marathon, not a concert!

Cast in one long act, Christ on the Mount of Olives falls into six scenes and features three characters: Jesus (tenor), a Seraph (soprano), and the disciple Peter (bass). Casting Jesus in a singing role was still an “iffy” thing to do in an oratorio, although better accepted in the German tradition than in the Italian. In addition, there are choruses for soldiers, disciples, and a host of angels.

It is these angels who sing the oratorio’s Hallelujah Chorus (you didn’t think that Handel wrote the only one, right?). You can enjoy this wonderful chorus performed here by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, with three times as many singers as anything Beethoven could have imagined, an orchestra four times bigger than anything Beethoven ever could have hired, and a concert hall three times larger than what any royal could have erected in 1803.

Did Beethoven learn from Handel’s many oratorios? Yes, and he studied seriously with specific masters of Baroque techniques, so you will you will hear flashes of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus throughout. But telltale signs remind us that this is Beethoven’s music, not Handel’s. Listen for the strong orchestral underpinning of the vocal parts and interjections of orchestral motifs between the vocal phrases; listen too for contrasting sections (something a Baroque chorus with its aesthetic of expressing a single emotion per movement would not have done).

Can you imagine what Beethoven would say if he walked into this performance, with its musical grandiosity within such architectural majesty? Can you imagine what he would say if he knew that you, while reading this, could click something and have it brought directly into your home?

During this period of his 250th anniversary, playing a bit more Beethoven could add a nice flavor to your household. You’ll find a session called “What’s So Great About Beethoven” available here on the Professor Carol site where I go more deeply into select aspects of Beethoven’s life and music. And when Lent does arrive, Beethoven’s beautifully moving Christ on the Mount of Olives will be waiting for you to explore more deeply.

Finally, join us if you can for an informal Zoom gathering on Beethoven’s birthday, December 16 at 8 p.m. Eastern, with special guest violinist Ivo Ivanov.