The whirlwind starts Friday when I fly off for my first tour of the fall. On Sunday evening in Warsaw, I will meet the twenty-one people who chose this Smithsonian Journey’s tour with its innocuous name “Old World Europe.” The next morning we’ll launch into our itinerary—an energetic exploration of the history and culture of Eastern Europe.

In fact, the countries we will visit, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, are better served by the descriptive “Central Europe.” They are central, grouped around today’s Austria, with the Czech Republic actually lying west of the city where so much of Europe’s iconic culture originated, namely Vienna. In addition, we will spend three nights in that opulent capital shaped by Hapsburg wealth, absorbing the contrast between the massive facades on the Ringstrasse and the tender sites that steal our hearts in other places along our route (like Krakow).

There’s a special style of chaos that plagues a person before a significant departure. Perhaps you know it. This time, I have another plumbing crisis (problems stood in the wings when we bought this house a year ago; we just hoped they might wait until Act III to take the stage). But even with plumbing dramas, I find it easier to pack for Europe here than back in Texas. The nostalgic fragrance of autumn already wafts in the North Carolina air. I can envision a cool morning in Budapest far better from my wooded deck than from a Texas patio baked with August sun.

Generally, I arrive a day in advance of each tour. The extra 24 hours gives me a modest slice of time to do what I like best: strolling at my own pace through museums. Each trip I promise myself to seek out new museums (there are plenty). Yet I generally end up returning to the buildings that house my best-loved framed friends.

That means I will go straight to Warsaw’s Polish National Gallery and start with the paintings by Jożef Chełmoński (1849-1914). I’ve written elsewhere about Chełmoński’s iconic “The Stork,” where a peasant boy and man gaze at the sky while storks fly overhead.

Chełmoński created other mesmerizing depictions of birds, including a terrific one called Partridges in the Snow that is so well-known, it appears in parodies. For example, a major political or cultural figure might be shown feeding these birds, walking next to them, or even leading them along the path.

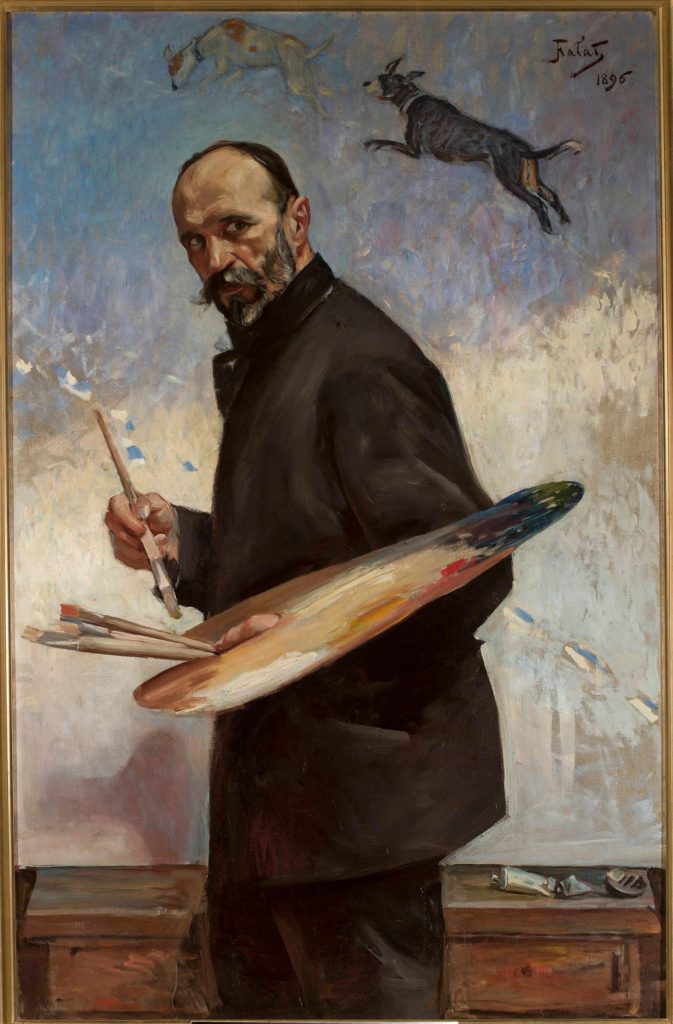

The painter whose works I visit after Chełmoński is Julian Fałat, another beloved Polish artist not particularly well known here in the US. Perhaps this is a good time to mention that the “l” with the cross in Polish (ł) is pronounced more-or-less like “w.” Would that this were the sole challenge presented by Polish consonants!

Fałat studied as a young artist in Munich. He also spent the year 1885 traveling through Europe and Asia. The following year, he received an appointment to Berlin as official court painter. But his heart dwelt in Poland, a land that, through most of his life, was not a nation. Rather, Poland had been reduced to a vestige of itself in the late 18th century when this once massive Renaissance kingdom was torn to pieces in three political partitions and taken by Russia, Prussia, and the Hapsburg Austrians. Poland recovered her independence as a nation only in 1918 in the wake of World War I.

Thus, for more than a hundred and twenty years between the final partitioning of Poland and her return to sovereignty, the task of defining Polish identity fell primarily to artists, from the ennobling polonaises poured out by Frédéric Chopin in his Paris exile, to Adam Mickiewicz’s sentimental poetry and chivalric epic Pan Tadeusz, to the bold landscapes and probing canvases of painters like Fałat.

No matter what it weighs, I am determined to return from this trip with a solid biography of Fałat. It will of necessity be in Polish, which gradually is becoming a usable language for me. But that’s the only way to learn details about his tenure in Berlin, as well as his ideas on art and Polish identity once he returned to his homeland and again breathed her sweet seasons at his villa in Bielsku-Białej. I’d also like to know how he responded, artistically, upon the restoration of an independent Polish nation on November 11, 1918.

Meanwhile, the story of Polish art is never quite finished. With so much looting and destruction during the Second World War (not to mention the upheavals during Communism), many things are still in disarray. Case in point: two significant paintings by Fałat placed for auction in New York City in 2010 were recognized, seized, and returned to Warsaw. Stories such as these remind us that the period required to recover from such disasters must be measured in centuries, not decades.

To end, let me share some thoughts penned by Jim Lane, a painter and admirer of Fałat, published on a site entitled Art Now and Then in 2014. Considering the difference in the process of painting nature (landscapes) and painting the interactions of humans within ordinary settings (genre paintings), he wrote:

In essence, God sets the stage for the landscape artist. Not unlike a screen writer or movie director, however, the genre artist must set the stage, provide the costumes, hire the actors, arrange them compositionally, facilitate the right lighting, and all of that before he or she draws the first line, much less begins deftly stroking pigment to canvas.

That’s it, isn’t it? A landscape, like the blazingly beautiful snowscapes by Fałat, is indeed staged by God, albeit captured by the talented eye and skilled hand of the painter. But the artist must execute a multi-faceted plan for a genre painting like Ash Wednesday (Popielec), agonizing about the details of the interior, fabrics and décor, positioning, expression, and human movement.

Perhaps this dichotomy helps explain why we humans can feel so oppressed by the circumstances and strictures of our daily lives, only to find instant refreshment when we experience nature. In nature, we walk into a drama created not by human hands, with all of the ensuing complications, but, rather, created by the Divine.