After taking up the cause of the subjunctive last week (thanks to all who wrote to add your hoorahs!), I promised a focus on art in my upcoming posts. You may be surprised by today’s starting point.

Summer foliage is about to yield to crimson and orange as we enter, arguably, the most evocative season of the year. Landscape painters rejoice in portraying spring, but autumn draws them deeper into their subjects. Or so it seems to me when I consider my favorite group of painters—Russian, Polish, and Hungarian—who hail from lands where winter perches in the wings, blowing its threats once September begins.

But before turning to these painters, let’s consider art lying right our fingertips: the illustrations in children’s books. Even without a vocabulary of analytical terminology, we and our children can still observe, comment, and draw a myriad of connections between the styles employed by illustrators of children’s book and the styles that characterize both our Western artistic heritage and art world-wide.

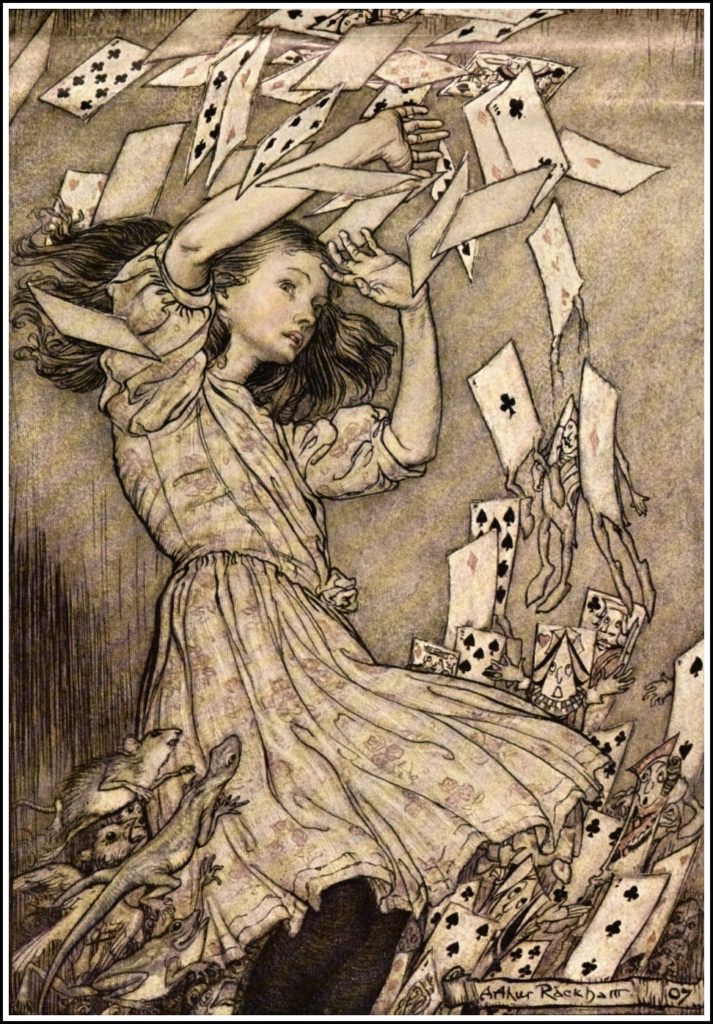

In my era, the pictures in Golden Books presented one mini-Norman Rockwell scene after another. It was, after all, an age of post-war optimism. Winged creatures and other magical beings sprang from fairy tales and the first wave of Disney books, but even those were rendered in traditional styles. Occasionally we came across books with more exotic styles of illustrations dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when artists like Arthur Rackham startled the eye of many a child (and adult) with his fantastic drawings. But by and large, little challenged us visually during story time.

Compare that with today’s children’s books! Nearly every page overflows with vivid, surprising illustrations that reflect virtually every style of representational and decorative art practiced around the globe. Even if the stories are vacuous, annoying, poorly written, or driven primarily by social agendas, the pictures accompanying them tend to be spectacular.

So why not use these illustrations to train our little ones (and ourselves) to develop an eye for art? I admit that I am still in the beginning stages of this journey. The visual aspects of children’s literature did not particularly draw my attention back when we raised our kids. But now, taking on the title of primary reader to our grandkids, I’ve rethought the role that such illustrations play in developing a child’s aesthetic judgment. Due to my own studies of the pedagogies of Classical education, I am seeing these illustrations through new eyes.

The best news is, you can start anywhere, from the detailed drawings (silly or not) in Dr. Seuss books or the beguiling cityscapes of Ludwig Bemelmans in the Madeline stories, to the bouncy figures in board books like The Little Blue Truck. Contrast any of these illustrations with the impact created by the stark pictures in Shel Silverstein’s The Missing Piece. (I still have not warmed up to that story, although there’s nothing better than his The Giving Tree to teach lessons on melancholy and emotional abuse, although I doubt that was Silverstein’s intention).

One thing for sure: using the illustrations in children’s books is a far less intimidating way to start a study of artistic style than using the so-called masterworks. Even if we lack the technical terms for what we see, we can still analyze and comment. And over a surprisingly short time, we will draw a myriad of connections between the styles employed by illustrators and those same styles that characterize our Western artistic heritage and art world-wide.

Recently, we reread Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs by Ron Barrett (story by Judi Barrett). One of the grandkids is old enough to make a gentle analysis of the pen-and ink-techniques used in the book’s hilarious illustrations, not to mention Barrett’s clever use of color. This brought up a discussion of the merits, and challenges, of pen-and-ink technique. Not surprisingly, this discussion was followed by the child’s feeble, but sincere, attempt to create a pen-and-ink drawing. What could be a better artistic exercise?

Plenty of books make use of “Impressionist” techniques, a surprising number of which focus on baby animals who are lost or otherwise puzzled by life. I’m not sure if I should draw concrete conclusions for the kids about that or not. It’s rarer to see the dark, bold strokes of Expressionist art shaping illustration in a child’s book, but it does happen, especially when the story told is drastic or dismal, and designed for upper elementary or middle schoolers.

I also love books where the illustrations are elaborate. We own a lovely copy of The Twelve Dancing Princesses retold by Marianna Mayer and illustrated by Kinuko Y. Craft. The capital letters on each page of text are rendered as a medieval-style illumination; the pictures themselves are placed in an interesting layout, sometimes with a secondary panel referring to, or magnifying, the main illustration on the opposite page, and sometimes sliced into thin columns placed at the edges of the pages.

I also adore our edition of Alexander Pushkin’s The Magic Gold Fish, adapted and illustrated by “Demi.” Here the text and pictures both are placed in large, thick bands of “O”s, either drawn in dark-gold color or formed by a ring of small, quaint figures that reflect the plot. To add to the visual power, the waves of the waterfront to which the beaten-down husband must go and present the magical fish with the ever-more outrageous demands of his wife change from a gentle lapping to furiously twisting lines. Even without a word of Pushkin’s text, we would know the curve of this plot.

Fascinating, too, are those books where the author serves as illustrator (you could, of course, reverse that statement). The two Shel Silverstein titles mentioned above are good examples. In that category too lie the Madeline books created by the copious talents of Bemelmans, as well as the original Dr. Seuss books (Theodor Geisel). Still, if asked to choose my favorite example of someone who overflows with both literary and artistic talents, I’d select Uri Shulevitz. His The Treasure and How I Learned Geography wow me, no matter how many times I open them.

Another thing to point out to kids is that artist partnerships sometimes arise where an author works solely, or largely, with the same illustrator, just as poets and composers team up (Rogers & Hammerstein, Gilbert & Sullivan, Mozart & da Ponte). The most famous example from my era would be the books by Margaret Wise Brown who partnered with artist Clement Hurd for her many famous titles including Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny. It’s fun, in these cases, to set multiple titles reflecting partnerships in front of older kids and have them search for prevailing visual characteristics that unite different books.

As always, the goal is to get the students (and ourselves) looking more deeply at visual works. Aim at evoking discussions, no matter how basic, about technical aspects (light, perspective, scale), physical materials (pen & ink, water-color style, imitative mosaic, photographic realism), and stylistic elements (cubist, Impressionist, Art Nouveau, Asian or Indian motifs). Furthermore, these observations for ourselves, made together with our children, actually carry over into the “real” world, helping us to analyze and appreciate everything from an architectural façade to a ragingly beautiful sunset. Art is life and life is art, the old saying goes. It’s true: we are empowered to embrace life more fully when art helps lead the way.

(This post includes affiliate links.)