I’m in Philadelphia, waiting to board a plane to Switzerland. The four-hour gap between my morning flight from Dallas-Fort Worth and my departure to Zürich seems a godsend.

Things have been moving like a whirlwind the past few days, including a brush with Hurricane Florence’s wrath on Sunday night that left a wet basement in our just purchased house in Winston-Salem. Let’s just say that we now know what happens when a sump pump hits a glitch.

But then, after sopping up water late into Sunday night, I flew down to Dallas on Monday and found myself seated happily that evening in the Richardson High School Band Hall, awaiting the final rehearsal of the Dallas Winds for their season opener on Tuesday.

The program included two ravishing vocal works sung by beauteous Hila Plitmman—one by John Mackey on texts expressing the devastation of the mythological figure Calypso as she bade farewell to Odysseus, and the other a delicate setting by Eric Whitacre of the children’s classic Good Night Moon. Bring on the Kleenex.

But at the top of the rehearsal’s agenda was a mad dash through Rossini’s William Tell Overture. Come on: who can resist this piece? It never loses its verve. Nor does it ever become easy, particularly at the tempo Maestro Jerry Jenkins conducted.

But at the top of the rehearsal’s agenda was a mad dash through Rossini’s William Tell Overture. Come on: who can resist this piece? It never loses its verve. Nor does it ever become easy, particularly at the tempo Maestro Jerry Jenkins conducted.

Still, hearing it resound through the hall brought me double pleasure. Nothing could have been more timely, as I’ve been preparing a talk on “William Tell” that I’ll give two days after I join my group in Switzerland.

You probably already know this, but William Tell was not a real person. Unlike many legends where an historical figure stands behind the story (like Johnny Appleseed), William Tell did not exist. It did not happen.

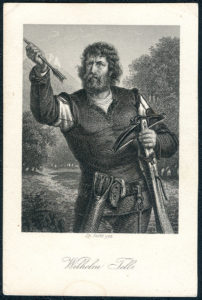

Overall I’m relieved that a poor dad was not forced to shoot an apple off his son’s head with a 15th-century crossbow. But without that legend, a huge hole opens up in Swiss historical culture. Simply put, the legend William Tell serves as one of two stories critical to the formation of the Swiss Confederation—a Willensnation that, to this day, is held together by agreement, despite significant differences in language, religion, and ethnicity.

The other story crucial to Swiss identity did happen: an oath taken around 1291 by representatives from three regions who agreed to band together and create a new geo-political entity (to use modern terminology). This oath gave rise to the term used for to describe Switzerland: Eidgenossenshaft, a body that exists at the pleasure of an oath.

Many a painter, silversmith, poet, and playwright has immortalized the legend of William Tell. In 1829, the mega-composer Giacomo Rossini created a lengthy operatic version of the story. Framed as what we call a French Grand Opera, it rose and fell on a series of dramatic scenes, including Tell’s arrest, the shooting under extreme duress of the apple off the boy’s head, a last-minute assassination of the oppressor, and a final victory chorus expressing the unity of the Swiss people. And to open up the whole shebang, Rossini wrote a spit-fire of an overture, probably recognized by more people than any other piece of classical music.

Also on the agenda for rehearsal was David Maslanka’s Symphony No. 5. Maslanka, who passed away last summer, integrated his love of the large-scale orchestral canvas by integrating extremely clever uses of traditional formal structures, including the style of hymn we call the Bach chorale. Maslanka also reveled in every opportunity to create contrasts in instrumental color and dynamics so intense that they leave the listener gobsmacked.

Well, that’s how the kids were reacting to it. What kids, you ask? The streams of high-school band kids who were passing through the side aisle of the band hall right about the time the second movement ended.

During rehearsals of the Dallas Winds in “their” band hall, these high-schoolers simultaneously are out on the football field, preparing everything from half-time shows to complex routines they will take to All-State competitions. When their practice ends, the kids respectfully file through the hall to the instrument-storage area in the back, put up their instruments, file out, and go home.

There were a lot of kids passing through on Monday night. The Richardson High band not only is huge, but has just been named one of the top ten high-school bands in the nation. They’re good, they’re proud, and they work hard.

I wish I could photograph their faces as they walk by. Usually they pass through gingerly, but coolly (they are high-schoolers, after all), holding their instruments carefully in front as they weave between the players. But always their faces are fixed to the side, watching these “grown-ups” who, to them, must seem terribly old. Teenagers cannot imagine ever being so old. But, oh, to play like that! To play at such a level of virtuosity. To play such fascinating and difficult repertoire!

But this time, when the third movement started, they didn’t keep walking. They stopped dead in their tracks. This time they were bowled over by the pianissimo virtuosity of the solo euphonium player Donald Bruce who guides the listener through this elegant third movement. These students are advanced enough to know that such sustained, beautiful sounds can be produced only by the power of mature lungs and a finely tuned embouchure. They simply cannot play like this yet. But they want to.

You could see the dreams in their faces. Maybe one day they will produce such sounds. Maybe one day they might make it into the Dallas Winds, returning regularly from their professional posts across Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma to play in this prized ensemble.

That after all is what has drawn me here this night, despite now living far away–this terrific ensemble. I don’t bring a horn, but I do bring my laptop and a set of ideas to share with the curious pre-concert audience. Attendees at these pre-concert talks come because they want an insight into the works coming from the pens of today’s largely American composers who are creating a beguiling body of new music. It’s a music that soars and invites, challenges and astounds.

Much as Rossini’s overtures surely did in their own time. I don’t know what the equivalent to band kids would have been in Rossini’s day, but surely there were young players who tip-toed admiringly along the edges of his rehearsals. And they surely looked at the grown-ups performing and dreamed of the time they too would achieve a similar level of proficiency.

Well, I would try to connect all of this neatly back to the legendary figure of William Tell, except it’s time to board the plane. The jarring realities of the airport are interfering with the music dancing in my head. Jarring, too, is the thought that I’ll soon be crammed into a little seat (so glad not to be a tall man) and faced with the toughest choice I’ll have to make this week: to watch 3 movies or to sleep? I’ll let you know what happens.