Our ship’s in a lock. I’m watching from my cabin window as we rise slowly from a scary concrete vault into a bright horizon and then sail gently forward into the leafy verdure of the Germany countryside.

Our ship’s in a lock. I’m watching from my cabin window as we rise slowly from a scary concrete vault into a bright horizon and then sail gently forward into the leafy verdure of the Germany countryside.

Thoughts swirl in my mind—particularly one. Actually this thought is always on my mind, but somehow today, perhaps because of the quiet of river travel, it’s deeply on my mind.

People need the arts. They really do. At the very least, they need to discover tangible connections to the arts. Even the most basic connection can unleash a relationship that will grow and make a difference in an individual’s life.

What do I mean by a “connection”? A connection could be actual involvement in the creative side of the arts: learning to do something artistic (studying an instrument, writing a song or poem, crafting a piece of jewelry, or sketching a tree). But more significant, to me, are the connections that open doors to the arts. At that moment, a person discovers qualities that are relevant and inspiring.

Case in point. Yesterday, on the Elbe Princess—the riverboat where I’m journeying with my Smithsonian group from Prague to Berlin—I gave a lecture on Bach called The Thoroughly Modern Musical Life of J.S. Bach.

While reviewing the talk the night before, I realized how infrequently I speak about Bach. Liszt, Wagner, Monteverdi, Beethoven, Stravinsky, just about any other composer seems to come up. But rarely Bach.

“Hmm,” I thought. “Wonder how this will go over?” I began to doubt the efficacy of my talk. I shouldn’t have worried. The response was jolting. To be sure, I am often blessed by positive reactions but this one was exceptionally strong. Why?

It seems that people “know” they should revere Bach. They acknowledge Johann Sebastian Bach as a composer of epochal genius.

But that doesn’t mean they relate to him.

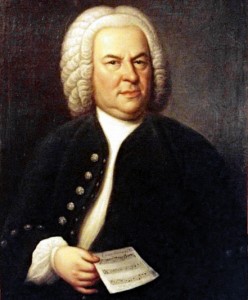

In a nutshell, people may revere him too much to see a realistic picture of a man who struggled through a sequence of jobs throughout his life. Actually, all artists do this. But with someone as famous as Bach, it’s hard for us to imagine such struggle. Bach looks so solid in those Baroque portraits, shrouded by his powdered wig and looking more like a headmaster than an artist.

The reality of Bach’s life was different. The sequence of his jobs called the “Stations of Bach” (think of a soldier stationed somewhere) tells a mixed story. Some of his stations were fulfilling and others brought trials. Some allowed him the maximum creative freedom while others hemmed him in due to the limited tastes of his patrons. Even the best jobs had unpleasant duties. Few jobs fed his desire to compose in the newest musical styles. Even fewer appreciated his extraordinary musical abilities.

He pleased as best he could. When possible, he sought out better positions. He often was disappointed when he did not get the top spot (Weimar, for example), or when his music-loving boss died and was replaced by a sovereign who did not care for music (Köthen).

So I needn’t tell you how much fun it was to present this talk. Quite a few in the audience had never thought of Bach as having struggles, or as being employed as a high-level servant, which is what every court, civic, or church musician was in the eighteenth century.

Bach striving for a better job or struggling to please a boss? Wasn’t he too lofty to be mired in such human dilemmas? These things matched up with events in their own lives. Several people told me they wanted to explore his music anew, or even for the first time.

My wish would be for each of us to build or discover paths that open up the arts. Maybe we build them carefully, or maybe we stumble into them. Particularly today, when so few receive an arts education, we need to have doors flung open as widely as possible. We need them flung open with an enthusiasm and warmth that says “Come on in: this is for you!”