In a talk I give at conferences called The Wrong Reasons to Teach Classical Music, I present what I believe to be an array of “right” reasons. Reason Number Six (in my countdown) involves the role music can play as our children study the Classical World of Ancient Greece and Rome.

In a talk I give at conferences called The Wrong Reasons to Teach Classical Music, I present what I believe to be an array of “right” reasons. Reason Number Six (in my countdown) involves the role music can play as our children study the Classical World of Ancient Greece and Rome.

The study of music can benefit these particular historical studies in several ways. First, it’s interesting for students to realize how music functioned in the Ancient world, in both social and religious contexts. Second, Western music theory is rooted in the Greek system, including the four-note pattern called the tetrachord that lies at the core of Greek musical scales. Third, attitudes that prevail still today about music are rooted in the Greek philosophical systems dealing with the ideas of ethos.

And finally, the instruments themselves can fascinate students.

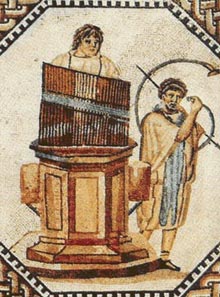

Mainstays of our musical instruments have roots that stretch back to the pre-Christian era and even earlier. Take the organ, for example. Our modern pipe organs are rooted in the celebrated Greek hydraulis, a high-tech invention that used water pressure to create the wind (pneumatic) power required to activate a set of pipes.

Its inventor seems to have been Ctesibius or Ktesibios of Alexandria. He was a Greek physicist and inventor around (285 – 222 BC). The son of a barber, he turned his curiosity into a quest to invent numerous items, including an early counter-balanced mirror and a variety of pumps.

In 1992, a total of nineteen bronze tubes from a first-century hydraulis were excavated at a city called Dion near Mt. Olympus. Specialists took these fragments and reconstructed an absolutely beautiful hydraulis. The level of technology and craftsmanship achieved so long ago is stunning!

Far more popular and widespread were the two main Greek instruments: the aulos and the kithera. The aulos is sometimes mistakenly called an “ancient flute” but it was a double-reed instrument, which puts it in the same family as the oboe and bassoon today. When a thin-walled, tubular cane reed is vibrated by air, a particularly human quality comes into the sound. Not surprisingly, the Greek aulos was used as an instrument to accompany and embellish epic poetry.

The kithera was a sophisticated stringed instrument that was played widely in Ancient Greece. A type of lyre, it was large and was used especially in public gatherings like theatrical performances.

The ability to play the kithera well was admired, but philosophers and educators warned against striving for too much facility (virtuosity).

Today, you can find recordings of these instruments (or, more correctly, modern reconstructions). Since only fragments of written-down (notated) Greek music have survived, your kids might ask how we know so much them? The answer lies in the visual record: sculptures, figurines, urns, bas reliefs, statuary. In fact, that’s perhaps the most fascinating thing about Ancient music. Specialists form ideas about one of the most fleeting things—sound—from objects that have withstood the centuries.

In my next post, I’ll move to what I consider even more useful about “ancient” music as it applies to our children’s modern-day education.